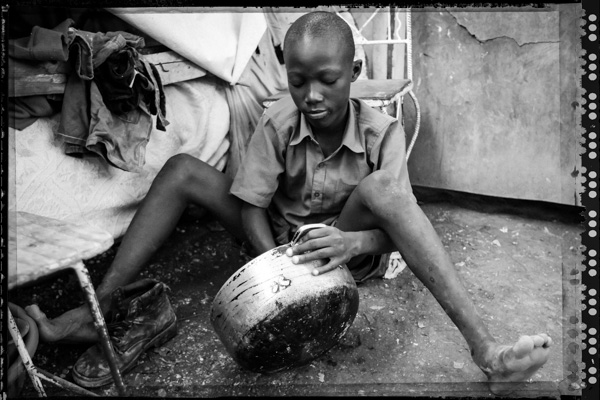

I have spent totally 20 months in Haiti since 2005. It’s the poorest country in the western hemisphere. You can see, feel and smell the poverty wherever you go. The hardships are enormous for the people and the hunger among the citizens is growing. The hair on broomstick-thin children has turned patchy and more orange, their stomachs have ballooned to the size of their heads and many look half their age; obvious signs of malnutrition, which is ravaging children, youngsters and babies.

Three years after an earthquake killed hundreds of thousands and international donors promised to help Haiti “build back better,” hunger is worse than ever. Despite billions of dollars from around the world pledged toward rebuilding efforts, the country’s food problems underscore just how vulnerable its 10 million people remain.

In 1997 some 1.2 million Haitians didn’t have enough food to eat. A decade later the number had more than doubled. Today, that figure is 6.7 million, or a staggering 67 percent of the population that goes without food some days, can’t afford a balanced diet or has limited access to food, according to surveys by the government’s National Coordination of Food Security. As many as 1.5 million of those face malnutrition and other hunger-related problems.

This is a scandal. This should not be. Much of the crisis stems from too little rain, and then too much. A drought last year destroyed key crops, followed by flooding caused by the outer bands of Tropical Storm Isaac and Hurricane Sandy.

Haiti has had similarly destructive storms over the past decade, and scientists say they expect to see more as global climate change provokes severe weather systems.

Haiti’s current hunger woes to decades of bad political decisions and, more recently, to last year’s storms and drought. Hunger is not new in Haiti. You can’t address the hunger situation in one year, two years. Long-term planning is needed, but there has to be some short-term actions as well. The government should work closer with big international organizations like UN, UNICEF, WFP, World Bank but also smaller NGOs from around the world working in Haiti.

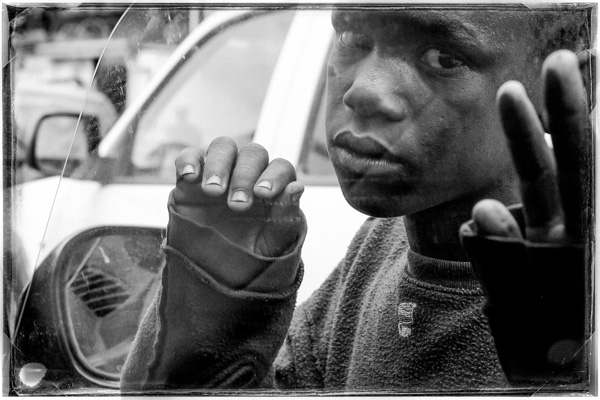

Many people have been forced to buy on credit, or look for the cheapest food available while eating smaller and fewer portions. Some families have asked relatives to take care of their children, or handed them over to orphanages so they have one less mouth to feed according humanitarian workers.

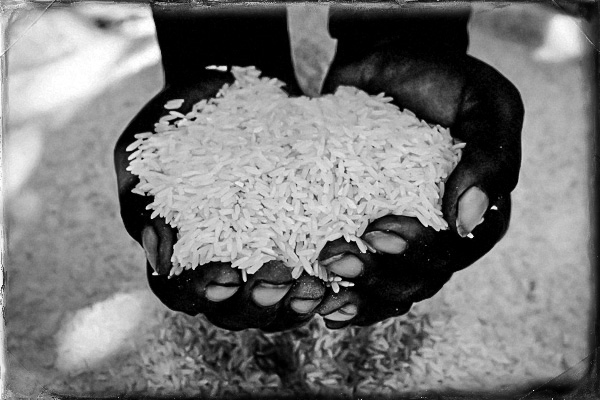

Political decisions already had hurt the ability of Haitian farmers to feed the country. One example: Prodded by the U.S. government, Haiti cut tariffs on imported rice from United States, driving many locals out of the market.

Eighty percent of Haiti’s rice — and half of all its food — is imported now. Three decades ago, Haiti imported only 19 percent of its food and produced enough rice to export. Factories built in the capital at the same time did little to help: They led farmers to abandon their fields in the countryside in hope of higher wages.

At the same time, Haiti has lost almost all of its forest cover as desperately poor Haitians chop down trees to make charcoal. The widespread deforestation does little to contain heavy rainfall or yield crop-producing soil.

With so much depending on imports, meals are becoming less affordable as the value of Haiti’s currency depreciates against the U.S. dollar. Haiti’s minimum wage is 200 gourdes a day. Late last year, that salary was equivalent to about $4.75; today it’s about $4.54 — a small difference that makes a big strain on the Haitian budget.

Hurricane Sandy ravaged the bean crops, leaving a three-month gap until the harvest resumed in December. With no beans to sell, farmers couldn’t buy rice, corn or vegetable oil.

The alarming situation has hurt education, too. Many children won’t go to school; they are too hungry to learn.

Especially hurt are children in Haiti’s hard-to-reach villages. Only the sturdiest off-road vehicles can climb the steep, twisting and rocky roads. Some villages are solely accessible by foot or donkey. Some children have to walk an hour or more to reach school, which is unacceptable if you’re hungry.

I have seen poor starving adults and children in many places in Haiti. I hate to see it. People shouldn’t be living like this!

Shortly after taking office, President Michel Martelly launched a nationwide program led by his wife, Sophia, called Aba Grangou, Creole for “end hunger.” Financed with $30 million from Venezuela’s PetroCaribe fund, the program aims to halve the number of people who are hungry in Haiti by 2016 and eradicate hunger and malnutrition altogether by 2025. Some 2.2 million children are supposed to take part in a school food program financed by the fund. This program works in some aspects, but it has far from been successful.

USAID has allocated nearly $20 million to international aid groups to focus on food problems since Hurricane Sandy, but villagers in southern Haiti said they have seen little evidence of that.

Will this regional hunger issues lead to nationwide starvation and even more food riots like a few years back?

Government officials concede that not all of the 44 areas have received food kits and other goods as part of the Aba Grangou program.

Haiti in general and the mountain villages in particular has long suffered from chronic hunger. Child malnutrition rates have been high for years. The United Nations’ World Food Program reports that nearly a quarter of Haiti’s children suffer from malnutrition.

What can be done to stop this ongoing disaster?

Maybe the rest of the world should stop meddling in Haiti.

How many times will we attempt to fix the problems the same ways we’ve tried in the past before we recognize they don’t work?

I agree!